A List by Tony Fyler

Before we begin and you all sharpen your pitchforks, as with the list of Top 5 Classic Doctor Who Stories, I know your mileage will vary. That’s both the point and the fun of a show that has run, with significant interruptions, for nearly 60 years – and for 18 years in its current format, which, because we’re a stubborn group of people, we’re still describing as “New Who.”

Enjoy what you enjoy. This list is merely my take on the Top 5 – it’s an invitation to go re-watch some epic, impressive television that you may not have seen in a while.

And, at the risk of further enraging sections of the fandom, this list contains no stories from either the Ninth or the Thirteenth Doctor’s eras. That’s nothing either personal or political – I love both eras. It’s just that, for my money, you get to a count of five pristine stories long before they start to get a look in.

As with the Classic Who list, these are not coming at you in any order of preference, but in transmission order, because each of them, in my view, is a glorious way to spend a chunk of your day, and I won’t sully that by ranking them further.

The Impossible Planet/The Satan Pit

The first time in New Who that space gets really gritty and grimy is on Sanctuary Base 6, in Matt Jones’ two-parter that pitches the Doctor and Rose against… your actual Devil.

There’s so much to love about this story, it could fill a review on its own. The creation of the Ood, with their vulvic faces and the red-eye syndrome borrowed – like a lot of the point of them in this story – directly from the equally high-class Robots of Death. The lessons about creating a slave workforce that outnumber you. The layering of impossibilities that make up the structure of the adventure – a planet in stable orbit around a black hole, a gravity corridor that allows ships to land on it, a drilling project in that location, and, did we mention, the literal freaking Devil at the bottom of it.

The layering of threat is similarly intense: the voice of the Beast, provided by Gabriel “Voice of Sutekh” Woolf; the avatar of the Beast – Toby Zed, whose murder of his fellow crewmate Scooti Manista is both cringy and chilling; the army of the Beast, in the poor, telepathically swamped Ood; the omniscience of the Beast, able to root around in the darkest human memories and face people with their starkest fears; and of course, the body of the Beast, locked away in its CG prison. As well as which of course, there’s the collapse of the impossibility that keeps the planet where it is to contend with.

17 years on, The Impossible Planet/The Satan Pit is still tremendously powerful Doctor Who, as each of the guest cast invest their characters with believable life, the threat level is obscenely high, and the pace rarely slackens, while also giving several moments their head in terms of delivering the creepy scares.

Oh and also, it’s the first time they used a quarry in New Who, so there’s that too. The two-parter stands up incredibly well, and is worth a re-watch if you haven’t seen it recently.

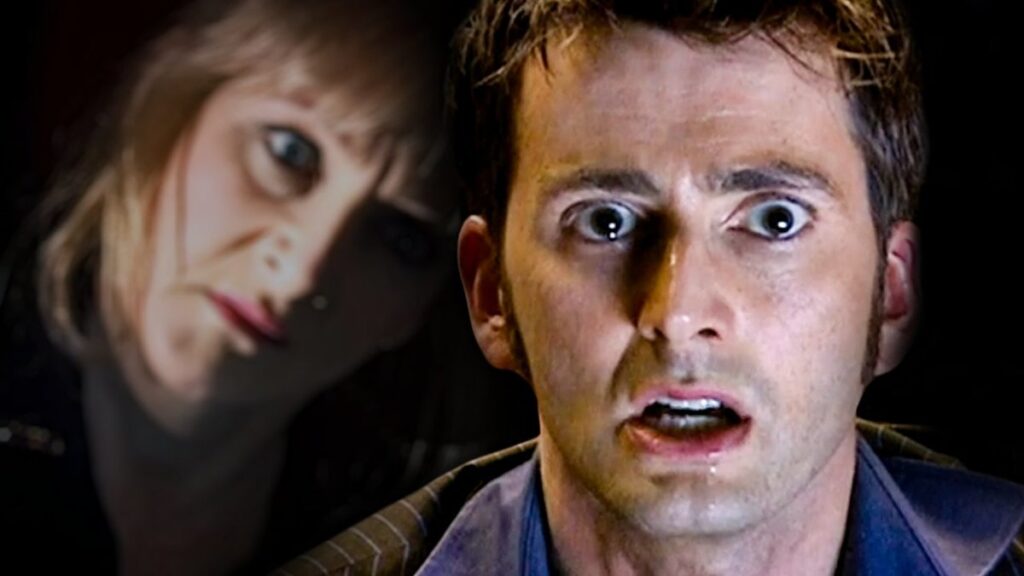

Midnight

The Tenth Doctor was nothing if not a chatterbox – the power of speech, and independent speech at that, was probably more important to him than it has been to several other incarnations.

So to rob him of his usual companion and stick him on a regularly scheduled “bus trip” across a tourist planet is an annoyingly good idea from the start.

And then the layering starts.

First of all, the Doctor is an unsupervised kid with an entertainment kill switch, so there has to be more active conversation than you’d normally get on such a trip. That’s enough to explore several less than happy relationship dynamics – Professor Know-It-All Hobbes (David Troughton) and his put-upon assistant Dee Dee Blasco (Ayesha Antoine), the quarrelsome Crane family, including their despairing son, Jethro (Colin Morgan), Sky Silvestry (RTD stalwart, Lesley Sharp), who’s trying to forget or bury her personal heartache, and the hostess, Rakie Ayola, keeping a brulee-thin crust of professional civility on top of her “I don’t get paid enough for this” attitude to troublesome passengers like the Doctor.

What could possibly go wrong?

Practically nothing, to be fair – that cast and Davies’ writing delivers all the fun and the tension that can be wrung out of getting a bunch of characters like that together in a small, claustrophobic space in what is essentially a toxic external environment.

Then things start to go classically bad. A flash of something barely seen out in the wilderness of the planet called Midnight, where nothing can possibly live.

An impact that tears the front off the “bus,” killing the pilot and the engineer, strands them all in the hostile environment, and then the bangings begin – danger instilled through sound and reaction alone – and the tone of the whole episode shifts as you forget to breathe between slams of impact on the outer hull.

And then the terror goes up a gear again, as Sky Silvestry starts mimicking the other passengers, and then homes in on the Doctor, saying what he says, even when what he says is totally random or especially meaningful. It’s schoolyard game as chilling Who, the repeating game that has driven many a parent to their wits’ end made especially sinister because it’s the Tenth and chattering Doctor, who for instance has brought down Harriet Jones’ government – elected by a landslide majority – with “just six words.”

When his words are stolen, and then pre-empted, the whole thing takes a further turn, as the nature of the entity that lives on Midnight is revealed to be increasingly creepy the more it learns to do.

And Midnight takes one further turn to the dark side before it sets us free – a kind of Lord of the Flies scenario from whom no-one can especially escape unscathed, as humanity, the species for which the Tenth Doctor so frequently expresses his love, turns on him, tries to eject him from the shuttle as either a solution or a sacrifice until the hostess figures things out.

Midnight is horror-movie Who at its finest, and the fact that the monster is never seen, and never speaks with its own agenda throughout the story, adds to the mythic, naturalistic terror of the thing. Give it a re-watch today and remind yourself why you only ever watch it in daylight.

A Christmas Carol

This one comes with a slight confession. My journey to acceptance of Matt Smith was a bit of a rollercoaster. On the reveal show, he seemed fascinating as a human being. The leaked audio from Victory of the Daleks made him sound to me like a parody Doctor – addressing Bracewell as “Prof” and all that. The reveal of his tweedfest depressed the living daylights out of me.

But there in The Eleventh Hour, he was spectacular, and bright, and winning, and wonderful…

Right till the end.

“Basically… run.”

That froze me on Matt Smith for the whole rest of his first series. Because it’s not the Doctor – not in any incarnation bar the as-yet-undreamed-of War Doctor. That’s not the Doctor, the cleverest life-form in the room, defeating the bullies. That’s the Doctor as the bully. That’s “Look at me. You can come and have a go if you think you’re hard enough, but you’re not, and I’ll hit you harder than you can imagine if you try.”

Forgive me my whims, but it landed very differently to David Tennant’s “It is defended!” And while there’s plenty of great Matt Smith action in Series 5, I was frozen on it by this quick way out of the problems of the universe (which in fairness, had been pioneered by Steven Moffat in Forest of the Dead). I’d argue that if the Doctor has too big a reputation, the villains lose their potential and their power – but that’s an argument for another day.

It’s worth noting though that the Eleventh Doctor would use that same bullying tactic time and again – in The Time of Angels/Flesh and Stone, at the Pandorica, and ultimately, it catches up with him in A Good Man Goes To War, and has to be addressed. By the time he reaches The Time of the Doctor, he’s become the defender of the universe again, and while the “Come and have a go if you think you’re hard enough” vibe is still there, it’s defensive at last, rather than threatening.

A Christmas Carol, to me, should come with the sub-title How I learned to stop worrying and love the Eleventh Doctor. It certainly gave me that moment when you look at a Doctor and go “Oh, there you are.” And it delivered a Doctor Who story that kicked against the usual “easy” strictures of good people and bad people. It made the Doctor a much more mercurial, silly, wonderful figure again, gave the Ponds a cosplay-heavy space-honeymoon, invented a world where sharks swam in the atmosphere, and brought Michael Gambon into the Doctor Who fold (for all he wasn’t particularly happy with his performance).

More than any of that though, it took us forward from the Doctor as he’d been for much of the first series of the Eleventh incarnation – either, as in The Eleventh Hour and the Angels two-parter, essentially bullying from a position of superiority, or, as in The Beast Below and Victory of the Daleks, depending on Amy Pond to be the better person and get him out of sticky situations.

In A Christmas Carol, what we get is a Doctor with tons more twinkle, but also, a Doctor much older than he seemed, trying a different approach to the usual, because he saw the spark of redeemable humanity in Kazran Sardick, even if it was a spark the rest of the world could never see.

That combination of the twinkly loon and the solemn thinker who wanted an easy life but was prepared to go the distance to solve complicated cases makes A Christmas Carol especially redemptive for me, as well as being decently bonkers, showing the Eleventh Doctor’s connection with children of whatever age, bringing the wonder of sky-sharks to the screen, and elevating Steven Moffat’s first Christmas special above many of the other festive specials that have studded the New Who era.

Quite apart from which, the idea of both people and holidays being “halfway out of the dark” is a philosophical truth that’ll stick with you long after the vegan turkey salad’s been thrown out as a lost cause.

The God Complex

I’m punishing myself here, because I’m allowing myself only one Capaldi story, despite Capaldi being the “favourite Doctor” I tell people I’m too old to have any more.

But The God Complex is intensely un-ignorable.

First of all, it’s written for the full range of the Eleventh Doctor’s personality – from joy at the detail in a cheese-plant to that kind of weary understanding when he finds what’s in his room, to the endless hope and appreciation for people like Rita (Amara Karan), to utter fury and the catharsis of smashing things, to rage, to pity, to love. Seriously, even on the page, Toby Whithouse’s script is a dream.

At least as much as that though, the direction by Nick Hurran judders you into discomfort very early on, and absolutely will not let you go. When you watch it, it’s never Who “as normal.” It demands a price of attention, and you pay it because you know it’s going to reward you tenfold.

There’s a lot for Hurran to work with – the premise is part Fawlty Towers, part The Shining, with every room filled with personalized horrors. Even just that in the right hands would be enough to make an unforgettable episode of Doctor Who.

Add to that a wandering minotaur, and the deeply creepy change that comes over people in the hotel once they’ve been in their room, the exultation that drives out fear and makes them welcome consummation with a gleeful “Praise him!” and you have an episode that, however it was directed, would probably give you enough of the creeps to let it stand tall in your memory.

But Hurran takes that whole bundle of factors and turbo-charges it with jitters and judders and creepy adoring smiles, intercut with screams. He wrings the psychological value out of the script and the performances, and delivers something truly mind-boggling.

Add that to an ending that undercuts a lot of what Doctor Who is based on – the idea of the Doctor being worthy of admiration from the people with whom he travels – and there are extra heartbreaking beats at the end, to cap the whole thing off and make it sing a mournful, glorious song.

It’s not a story to be re-watched too often, for fear of wearing it out and ending up complacent. It’s better than that, and The God Complex deserves respect at every level.

Heaven Sent

And finally, because I’m limited to five stories, the most predictable Capaldi choice you could ever wish for.

But the reason it’s predictable is because the story is so intriguing, and layered, and agonising. It’s the Doctor alone, with just the ghostly memory of Clara and the inevitable device of him talking to himself to spur both him and the story on.

It’s a story that advances, step by step and revelation by revelation, in a constructed environment that’s part steampunk, part Clive Barker puzzle box. The rules are simple, but because he’s truly alone, we get much more of an insight than usual into how the Doctor’s mind actually works – when he drops something, he’s assessing local gravity. Throwing a chair out of a window is a measure of distance between his location and the sea, and so on.

Part of the aching joy about the story is that more things work like that than the Doctor ever remembers on his route towards extinction and rebirth – the sea full of skulls, the wrong stars in the sky, and so on. Peter Capaldi had many fine moments and speeches and hours during his time in the Tardis. I bow to no-one in my appreciation of more or less the whole of Series 9, and that Zygon speech is pure, painful, flagellating, cathartic bliss.

But Heaven Sent is Steven Moffat’s masterwork as far as his Capaldi episodes are concerned. It feels stripped back, bleak, and honest in terms of grief – and what that means for a Time Lord. It’s confession, purgatory, punishment all in one, but it’s also the dogged continuation on the way to a surprise ending. There’s more or less always that combination of morbidity and humour in Capaldi’s Doctor, and here it’s much more skewed towards straight up melancholy.

You couldn’t do Doctor Who like this more than once in a very blue moon – but that doesn’t mean that if you get it right, it can’t be wonderful.

Heaven Sent is as wonderful as it needs to be, and then more wonderful still. It’s contained but with consequences, a tour de force for Capaldi, and a pinnacle of his particular kind of Doctoring. If you haven’t watched it recently, go and be kind to yourself. Heaven Sent is self-care of a wondrous and melancholy quality. If, to quote from another Moffat story, “sad is happy for deep people,” Heaven Sent is destined to make those people very, very happy for the rest of time.

Be the first to comment on "The Top 5 New Doctor Who Stories"