Screenplay by: Peter Atkins

Directed by: Anthony Hickox

Something strange tended to happen to big Eighties and Nineties horror franchises when they hit their third movie.

Friday the Thirteenth, Part III was both a direct sequel to the second movie and gave us a definitive look for Jason Voorhees (Enter the Hockey Mask), which would be his identifying characteristic until the end of time. It was also released in 3D, making the most of its 3-ness in the saw way Jaws 3-D did.

Halloween III took us away completely from the Michael Myers slashfest schtick and tried something else entirely, with the initial idea of turning the Halloween franchise into something more inventive and anthology-based than any other set of horror movies. It didn’t ultimately work, but it was an interesting idea at the time.

A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors massively expanded the mythos and the nature of its central villain, Freddy Krueger, and started to develop ways that ordinary mortals could become more than just fresh meat on his nightmare table.

Hellraiser 3: Hell on Earth picks a little from each of columns A, B, and C and while in hindsight, people might scoff at its expanded premise, watched 31 years on from its initial cinematic release, it hangs together remarkably well.

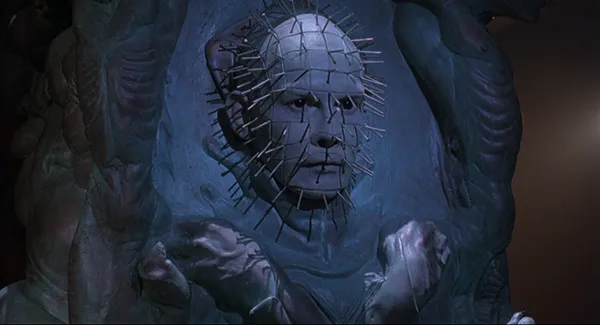

Where Hellbound: Hellraiser II felt like a roughly-hewn re-tread of the cast and issues of the original iconic movie, Hellraiser III brings a whole new philosophy to the Cenobite legend of the first two films and gives us something we’ve never seen before – Pinhead separated from his Hellish majesty and his crew of acolytes. Pinhead immobilized and trying to regain his physical form. Pinhead on Earth. And perhaps most importantly of all, Pinhead splintered, with his pre-Hell identity, Captain Elliot Spencer, separated out after his revel in the second film, and actively working against his Hellish identity.

That’s a whole lot of new ground for the Hellraiser mythos to cover.

A New Nightmare?

But what’s at least as important about Hell on Earth is that it does the same sort of thing that A Nightmare on Elm Street 3 does – it sets up the franchise for broader, more episodic adventures in the dark, and it centres the evil on a much more funny, sadistic, persuasive version of the chief antagonist – Freddy in Elm Street, Pinhead in Hellraiser.

In the first two Hellraiser movies, Pinhead is implacable, beyond humanity, an ultimate expression of darkness, for all we understand he was once human in the second film. In Hellraiser 3, the performance from Doug Bradley is very different. For one thing, he gets significantly longer on-screen than he does in the first two movies, because he’s very much become the centre of the action.

And if you give a villain much more screen-time, you’re going to need them to say more and do more. Where Freddy transforms in the third movie from dark avatar of body horror and injustice to wisecracking supernatural serial killer, in some cases literally toying with his victims in ever-more inventive ways, Pinhead follows in Hellraiser 3.

First, we have him trapped in a statue, a rendering of the revolving torture block which adds victims to itself as he manages to acquire them. But then, we see the utterly ruthless nature of Pinhead as a survivor, going from his usual declaratives – “We’ll tear your soul apart!” etc – to a much more wheedling, persuasive, almost whispering, seeing inside his potential victims’ minds to unleash their darkest and deepest desires. When he makes a deal with degenerate club-owner JP Monroe for the latter to bring him victims, that’s Plan A, but when one of the potential victims, Terri, gets the upper hand, he instantly changes tack, persuading her to feed him Monroe instead.

When Pinhead reaches full corporality again, he quickly goes full-on torture-chamber in downtown New York, turning Monroe’s nightclub into a charnel house with his signature hooks and chains.

Where much of Hellraiser II was taken up with the agonising, long process of a human more or less earning the right to become a Cenobite, here, there’s a much more throwaway, almost TV movie approach, showing Pinhead in a hurry to replace his original acolytes.

Yes, the original Cenobites, who we saw slaughtered by the Channard Cenobite in the second movie, appear to be genuinely dead – So long Butterball, arrivederci Chatterer, and farewell the ever-unnamed Female Cenobite, though she’s replaced her with the Dreamer Cenobite, giving the powers of Hell a new dimension, and again one that chimes with the third Nightmare movie, in their ability to invade people’s dreams.

Pinhead, without reference to Leviathan, who seemed to be in control of the Cenobite-making process in movie 2, makes not only Monroe and Terri into members of his new crew, but also adds a little heft to the group with a TV cameraman, who gains a Terminator-style camera-eyeball with offensive capabilities, a drummer who gets CDs embedded in his head and then, in his Cenobite life, starts inflicting the same punishment on his victims, and a drunk who gains the ability to breathe fire.

If that all sounds a little second rate and shark-jumpy, it’s because we haven’t yet discussed the other main string in the movie’s bow.

Terry Farrell, who would join the crew of new Star Trek variant Deep Space Nine the following year as Jadzia Dax, takes the place of Kirsty Cotton as our chief protagonist, and right from the off, she gives the central role of Joey Summerskill, journalist, more dramatic heft than Cotton ever had.

Yes, it’s still “early Nineties woman as potential victim” territory, but Farrell straddles an interesting line of strength and vulnerability that makes her compelling on screen, in a way which Kirsty’s lack of purpose beyond the story never allowed her to be.

Joey has dreams of the Vietnam War, where her father died before he could ever see her. She’s almost literally haunted by the notion of him being alive when he was abandoned by a helicopter, left to bleed out and die on a stinking battlefield thousands of miles from home.

Enter Captain Elliot Spencer, the Pinhead-before-Pinhead, survivor of an earlier battlefield, and in a very economical handful of sentences, he explains what led him to the LeMarchand box, to Hell, and to his destiny as Pinhead.

While it’s possible to claim this is rather too much exposition, it never feels like too much in the movie, and the duality-yet-sameness of Spencer and Pinhead goes on to become a major theme, and one that helps Joey send Pinhead back to Hell, rather than, as is his intent, to roam the streets of first New York, and ultimately the Earth, turning it into a Cenobite-filled cesspit of pain and suffering.

Freedom To Breathe

The bottom line of all of this is that Hellraiser 3 loses some of the first movie’s strangeness, gives Doug Bradley a double role, and amps up the grotesquerie and smart mouth of Pinhead to make him ever so slightly more cinematic and weirdly relatable – playing around with notions of religion by giving himself stigmata with one of his own brain-pins and feeding a priest his own dark communion is melodramatic, maybe, but it’s melodramatic in a very human way, rather than for instance, all the insectoid creep-outs of the more traditional Hell from the first two movies.

It also, for the first real time, gives Pinhead a protagonist who’s prepared to do what’s necessary – side-note, it’s Terry Farrell’s Joey who first calls Pinhead “Pinhead” on screen – and dabbles in the esoteric notion of good and bad combined in one person, and how their separation can be both psychologically interesting and make for a significant plot engine, as in The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, by Robert Louis Stevenson. If Pinhead is chattier and potentially reduced by that in the third movie, it’s worth looking at his portrayal as being the wild evil that lurked in Elliot Spencer, unfettered by his own particular pain and gravitas.

Overall, while the Cenobites may be less interesting and less in line with their established BDSM chic here, it’s because they become very much secondary players to the dramas of Elliot Spencer, Pinhead, and Joey Summerskill – and, as there was enough drama in the character dynamics between Frank, Julia, Larry and Kirsty in the first movie to prop up the 8 minutes or so of outlandish Cenobite action, so there’s enough that’s worth knowing about the character dynamics of the three central playters in this movie to support at least Pinhead’s return and rampage through New York.

Is Hellraiser 3 worth re-watching as part of the Quartet of Torment box set? Beyond words, yes. While it might feel to some Barker purists like a relatively trashy interpretation of his themes and imaginings, it has a lightness and a narrative thrust that the second movie distinctly lacks, and the performances are strong enough to carry the action through.

While it lacks the determination to tease you into what the fourth movie actually became, it does deliver an interesting ending that suggests the evil of the LeMarchand box has a potential to influence all those around it, and makes you wonder about the notion of the relationship between objects and the human psyche. Do we know we like pain before the first whip is applied, the first needle inserted? The ending of Hellraiser 3 makes us consider that relationship, but in a bigger sense – the connection between human psychology and the built environment – which is absolutely explored in Hellraiser: Bloodline.

The extras for the third movie are slightly less chunky than they are on the first two, but there’s a solid collection of archival interviews (including one with Bradley about his third outing in the head of pins), and some excellent audio commentaries. If we’re being picky – and why not, it’s what critics have instead of a soul – it would have been joyous to catch up with Terry Farrell to get her views on the film and where it sits in her career, but beyond that, the Quartet of Torment release of Hellraiser 3 is arguably more of a must-have than, say, the version of Hellbound: Hellraiser 2 in the set, dripping with extras though that second film is.

In fundamental terms, Hell on Earth is a shift away from the claustrophobic tone of the first two Hellraiser movies, and while some will see that as its greatest flaw, it centres Pinhead as the chief bad guy, has interesting things to say about trauma, pain, and a desire to explore sensation, and gives the franchise a pathway from its beginnings to something longer and broader than the original premise allowed. For that, and for all the fun along the way, Hellraiser 3 is worth a re-watch in the beautiful beautiful Quartet of Torment set. Tony Fyler

Be the first to comment on "Hellraiser – Quartet of Torment: Hellraiser III: Hell On Earth"